5.3 Fonction dérivée et règles de dérivation

Si \(f\) est définie sur un intervalle ouvert \(I\), \(f\) est dite

dérivable sur \(I\) si \(f\) est dérivable en tout point de \(I\). On

définit alors la fonction

\[f'(x):=

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\,,

\]

appelée la dérivée de \(f\) sur \(I\).

Notation équivalente: \(f'\),

\(\frac{df}{dx}\) (notation de Leibniz).

Exemple:

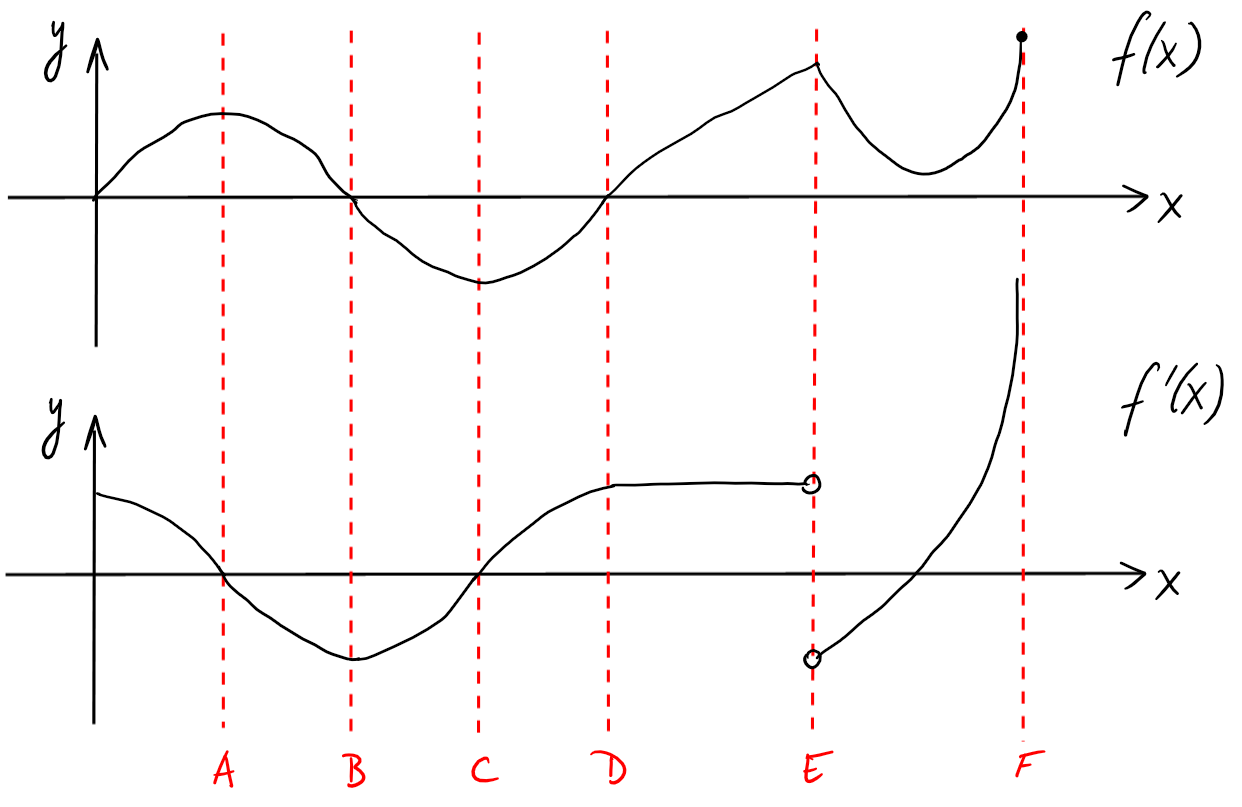

Représentons une fonction \(f\) et sa dérivée \(f'\).

- Au point \(A\), la fonction \(f\) arrête de croître et commence à décroître. La dérivée \(f'\) est donc \(\gt 0\) avant \(A\) et \(\lt 0\) après.

- Au point \(B\), \(f\) décroît le plus rapidement et donc la dérivée y a un minimum.

- Au point \(C\), \(f\) arrête de décroître et commence à croître. La dérivée passe donc de \(\lt 0\) à \(\gt 0\).

- Au point \(D\), \(f\) croît le plus rapidement. \(f'\) y a donc un maximum.

- Au point \(E\), la fonction \(f\) n'est pas dérivable, et la fonction \(f'\) n'est donc pas définie en ce point.

- Au point \(F\), \(f\) n'est pas dérivable et la tangente y est verticale. \(f'\) tend vers \(+\infty\).

Règles de dérivation

Théorème:

Soient \(f\) et \(g\) dérivables sur \(I\). Pour tout \(x\in I\),

- \((f+g)'(x)=f'(x)+g'(x)\),

- \((\lambda f)'(x)=\lambda f'(x)\), \(\lambda\in\mathbb{R}\),

- \((f\cdot g)'(x)=f'(x)\cdot g(x) + f(x)\cdot g'(x)\),

- Si \(g(x)\neq 0\),

\(\displaystyle

\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(x)=\frac{f'(x)g(x)-f(x)g'(x)}{g^2(x)}\)

Si \(f\) est dérivable en \(x\) et \(g\) et dérivable en \(f(x)\), on a aussi

\[

(g\circ f)'(x)=g'(f(x))\cdot f'(x)\,.

\]

Preuve:

-

\[\begin{aligned}

(f+g)'(x)

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(f+g)(x+h)-(f+g)(x)}{h}\\

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)+g(x+h)-f(x)-g(x)}{h}\\

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}+\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{g(x+h)-g(x)}{h}\\

&=f'(x)+g'(x).

\end{aligned}\]

-

\[\begin{aligned}

(\lambda f)'(x)

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(\lambda f)(x+h)-(\lambda f)(x)}{h}\\

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\lambda f(x+h)-\lambda f(x)}{h}\\

&=\lambda\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\\

&=\lambda f'(x)\,.

\end{aligned}\]

(Cette propriété peut aussi être vue comme une conséquence de la suivante, où

une des fonctions est prise comme étant constante.)

- Par définition,

\[

(f\cdot g)'(x)=

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(f\cdot g)(x+h)-(f\cdot g)(x)}{h}\,.

\]

Récrivons le quotient comme suit:

\[\begin{aligned}

&\frac{(f\cdot g)(x+h)-(f\cdot g)(x)}{h}\\

&\qquad=\frac{f(x+h)g(x+h)-f(x)g(x)}{h}\\

&\qquad=\frac{f(x+h)g(x+h){\color{blue}-f(x)g(x+h)+f(x)g(x+h)}-f(x)g(x)}{h}\\

&\qquad= \frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}\cdot g(x+h)+

f(x)\cdot \frac{g(x+h)-g(x)}{h}

\end{aligned}\]

Dans cette dernier ligne, les quotients convergent

respectivement vers \(f'(x)\) et \(g'(x)\). Puis, comme

\(g\) est dérivable, elle est continue en \(x\), et donc

\[

\lim_{h\to 0}g(x+h)=g(x)\,.

\]

Ceci implique que

\[

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{(f\cdot g)(x+h)-(f\cdot g)(x)}{h}

=f'(x)g(x)+f(x)g'(x)\,.

\]

- En procédant comme dans le point précédent,

\[\begin{aligned}

\left(\frac{f}{g}\right)'(x)

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\frac{f(x+h)}{g(x+h)}-\frac{f(x)}{g(x)}}{h}\\

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot g(x+h)}{h\cdot g(x+h)\cdot g(x)}\\

&=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)\cdot g(x) -f(x)\cdot g(x) +f(x)\cdot g(x)-f(x)\cdot

g(x+h)}{h\cdot g(x+h)\cdot g(x)}\\

&=\frac{1}{g(x)}\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{1}{g(x+h)}\cdot \lim_{h\to 0}\left[g(x)\cdot\frac{(f(x+h)-f(x))}{h}-f(x)\cdot \frac{(g(x+h)-g(x))}{h}\right]\\

&=\frac{1}{g(x)}\cdot \frac{1}{g(x)} \cdot (g(x)\cdot f'(x)-f(x)\cdot g'(x))\\

&=\frac{g(x)\cdot f'(x)-f(x)\cdot g'(x)}{g^2(x)}.

\end{aligned}\]

Dérivées de puissances

Voici quelques exemples de dérivées des fonctions élémentaires.

Remarquons pour commencer que si une fonction \(f\) est constante,

\(f(x)=C\) pour tout \(x\), alors sa dérivée est nulle puisque

\[

f'(x)

=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h}=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{C-C}{h}=0\,.

\]

Théorème:

Soit \(n\in \mathbb{Z}\). Alors

\[ (x^n)'=nx^{n-1}

\]

(Si \(n\) est négatif, \(x^n\) n'est bien sûr pas définie en \(x_0=0\).)

Preuve:

Commençons par les exposants entiers positifs, \(x\in \mathbb{N}^*\). On procède par

récurrence sur \(n\).

Lorsque \(n=1\), \(f(x)=x^1\), et donc

\[

(x^1)'

=\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{(x+h)^1-x^1}{h}

=\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{(x+h)-x}{h}

=\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{h}{h}

=1\,.

\]

Puisqu'on peut écrire cette dernière comme

\((x^1)'=1\cdot x^{1-1}\), on a démontré le résultat pour \(n=1\).

Supposons que pour un certain \(n\in \mathbb{N}^*\), \((x^n)'=nx^{n-1}\).

Pour \(n+1\), on peut écrire \(x^{n+1}=x^n\cdot x\), et

utiliser la règle de dérivation d'un produit:

\[\begin{aligned}

(x^{n+1})'

&=(x^n\cdot x)'\\

&=(x^n)'\cdot x+x^n\cdot (x)'\\

&=nx^{n-1}\cdot x+x^n\cdot 1\\

&=nx^n+x^n

=(n+1)x^n

=(n+1)x^{(n+1)-1}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Donc la formule est aussi vraie pour \(n+1\).

Si on considère maintenant \(n\in \mathbb{Z}\), \(n\lt 0\), alors \(m=-n\in \mathbb{N}^*\), et

donc par la règle de dérivation d'un quotient,

\[\begin{aligned}

(x^n)'=

(x^{-m})'

&=\left(\frac{1}{x^m}\right)'\\

&=\frac{-(x^m)'}{(x^m)^2}\\

&=\frac{-mx^{m-1}}{x^{2m}}\\

&=(-m)x^{-m-1}=nx^{n-1}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Exemple:

\((x^{1234})'=1234\cdot x^{1233}\)

Considérons une puissance non-entière, comme \(\frac12\):

Exemple:

Si \(x\gt 0\),

\[\begin{aligned}

(\sqrt{x})'

&=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{\sqrt{x+h}-\sqrt{x}}{h}\\

&=\lim_{h \to 0}\frac{1}{\sqrt{x+h}+\sqrt{x}}\\

&=\frac{1}{\sqrt{x}+\sqrt{x}}\\

&=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{x}}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Remarquons qu'avec un exposant,

\(\sqrt{x}=x^{1/2}\), cette dernière prend la forme

\[ (x^{1/2})'=\tfrac12 x^{\frac12-1}\,.

\]

La dernière remarque suggère que

la formule donnée dans le théorème précédent est aussi valable

pour des exposants rationnels.

Théorème:

Soient \(p\in \mathbb{Z}\), \(q\in\mathbb{Z}^*\). Alors

\[ (x^{\frac{p}{q}})'=\tfrac{p}{q}x^{\frac{p}{q}-1}\,,\qquad x\gt 0

\]

Preuve:

Commençons par le cas \(p=1\), \(q\in \mathbb{N}^*\).

On a

\[

(x^{\frac{1}{q}})'

= \lim_{\widetilde{x}\to x}\frac{\widetilde{x}^{1/q}-x^{1/q}}{\widetilde{x}-x}\,.

\]

Effectuons le changement de variable \(\widetilde{x}^{1/q}=\widetilde{y}\), \(x^{1/q}=y\):

\[\begin{aligned}

\lim_{\widetilde{x}\to x}\frac{\widetilde{x}^{1/q}-x^{1/q}}{\widetilde{x}-x}

&=\lim_{\widetilde{y}\to y}\frac{\widetilde{y}-y}{\widetilde{y}^q-y^q}\\

&=\lim_{\widetilde{y}\to y}\frac{1}{\frac{\widetilde{y}^q-y^q}{\widetilde{y}-y}}\\

&=\frac{1}{\lim_{\widetilde{y}\to y}\frac{\widetilde{y}^q-y^q}{\widetilde{y}-y}}\\

&=\frac{1}{q y^{q-1}}\\

&=\frac{1}{q (x^{1/q})^{q-1}}\\

&=\tfrac{1}{q}x^{\frac{1}{q}-1}

\end{aligned}\]

Maintenant, pour une valeur quelconque \(p\in \mathbb{N}^*\), par la règle de

dérivation d'une composée,

\[\begin{aligned}

(x^{\frac{p}{q}})'

&=\left((x^{1/q})^p\right)'\\

&=p(x^{1/q})^{p-1}(x^{1/q})'\\

&=p(x^{1/q})^{p-1}\tfrac1q x^{1/q-1}\\

&=\tfrac{p}{q}x^{\frac{p}{q}-1}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Dérivées des fonctions trigonométriques

Théorème:

Pour tout \(x\in \mathbb{R}\),

\[\begin{aligned}

(\sin(x))'

&=\cos(x)\\

(\cos(x))'

&=-\sin(x)\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Pour tout \(x\in \mathbb{R}\setminus\{\frac{\pi}{2}+k\pi,k\in\mathbb{Z}\}\),

\[

(\tan(x))'=

\begin{cases}

1+\tan^2(x)\,\text{ ou}\\

\frac{1}{\cos^2(x)}\,.

\end{cases}

\]

Preuve:

Par définition,

\[

(\sin(x))'

=\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h}

\]

On utilise la relation (voir Analyse A)

\[

\sin(x+h)=\sin(x)\cos(h)+\cos(x)\sin(h)\,.

\]

Après avoir réarrangé les termes, le quotient devient

\[\begin{aligned}

\frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h}

&=\sin(x)\cdot\frac{\cos(h)-1}{h}+\cos(x)\cdot\frac{\sin(h)}{h}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Or on a d'une part que \(1-\cos(h)\sim h^2/2\) au voisinage de \(h=0\), donc

\[

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\cos(h)-1}{h}=

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{-h^2/2}{h}=0\,,

\]

et d'autre part on sait que

\[ \lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\sin(h)}{h}=1\,.

\]

Ceci implique que

\[

\lim_{h\to 0}\frac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h}=\cos(x)\,.

\]

En utilisant ensuite les relations

\[\begin{aligned}

\sin(x+\tfrac{\pi}{2})&= \cos(x)\,,\\

\cos(x+\tfrac{\pi}{2})&= -\sin(x)\,,\\

\end{aligned}\]

on peut utiliser la formule pour la dérivée d'une composée comme suit:

\[\begin{aligned}

(\cos(x))'

&=\left(\sin(x+\tfrac{\pi}{2})\right)'\\

&=\cos(x+\tfrac{\pi}{2})\cdot\underbrace{(x+\tfrac{\pi}{2})'}_{=1}\\

&=-\sin(x)\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Finalement, par la règle de dérivation d'un quotient,

\[\begin{aligned}

(\tan(x))'=

\left(\frac{\sin(x)}{\cos(x)}\right)'=

\frac{\cos^2(x)+\sin^2(x)}{\cos^2(x)}\,,

\end{aligned}\]

que l'on peut simplifier avec \(\cos^2(x)+\sin^2(x)=1\), ou alors séparer en

\[

\frac{\cos^2(x)+\sin^2(x)}{\cos^2(x)}=

\frac{\cos^2(x)}{\cos^2(x)}+

\frac{\sin^2(x)}{\cos^2(x)}=1+\tan^2(x)

\]

Exemple:

\[

\left(\sqrt{\sin(x)}\right)'

=\frac{1}{2\sqrt{\sin(x)}}\cdot (\sin(x))'

= \frac{\cos(x)}{2\sqrt{\sin(x)}}\,.

\]

Dérivées exponentielles et logarithmes

Théorème:

Pour tout \(x\in \mathbb{R}\),

\[ (e^x)'=e^x\,.

\]

Pour tout \(x\in \mathbb{R}_+^*\),

\[ (\ln (x))')=\frac1x\,.

\]