8.4 Les matrices de passage

Motivation

Pour commencer, étudions les relations existant entre les composantes d'un

même vecteur, exprimé relativement à une base ou à une autre.

Avant de voir l'approche dans le cas général,

commençons par un exemple simple.

Exemple:

Dans le plan, considérons le vecteur

\[

\boldsymbol{x}= \begin{pmatrix} 5\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Considérons maintenant la base \(\mathcal{B}=\{ \boldsymbol{b}_1,\boldsymbol{b}_2 \}\), dont les

vecteurs sont disons

\[

\boldsymbol{b}_1= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\-1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

\boldsymbol{b}_2= \begin{pmatrix} 2\\1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Quelles sont les composantes de \(\boldsymbol{x}\) relatives à \(\mathcal{B}\)?

Ce qu'on cherche ici est

\[ [\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=

\begin{pmatrix}\beta_1 \\\beta_2 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

qui ne signifie rien d'autre que

\[ \boldsymbol{x}=\beta_1\boldsymbol{b}_1+\beta_2\boldsymbol{b}_2\,.

\]

Or cette dernière s'exprime comme

\[

\begin{pmatrix} 5\\1 \end{pmatrix}

=

\beta_1

\begin{pmatrix} 1\\-1 \end{pmatrix}

+\beta_2

\begin{pmatrix} 2\\1 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

qui est équivalent au système d'équations linéaires

\[

\left\{

\begin{array}{ccccc}

\beta_1 &+& 2\beta_2 &=& 5\,,

\\

-\beta_1 &+& \beta_2 &=&1\,,

\end{array}

\right.

\]

dont la solution est \(\beta_1=1\), \(\beta_2=2\).

Ainsi,

\[ [\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=

\begin{pmatrix}1 \\2 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

qui signifie \(\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{b}_1+2\boldsymbol{b}_2\).

Remarque: Il est plus utile de penser que \(\boldsymbol{x}\) est un vecteur dans

le plan, et que ce vecteur peut être représenté en composantes, relatives à

la base canonique \(\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\) ou à la base \(\mathcal{B}\):

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

\begin{pmatrix}5 \\1 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\qquad

[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=

\begin{pmatrix}1 \\2 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Bien-sûr, il serait intéressant d'avoir un procédé permettant d'obtenir

directement les composantes d'un vecteur quelconque dans une base, en fonction

des composantes dans l'autre base:

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

\begin{pmatrix}\gamma_1 \\\gamma_2 \end{pmatrix}

\overset{?}{\longleftrightarrow}

\begin{pmatrix}\beta_1 \\\beta_2 \end{pmatrix}

=[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}\,.

\]

Abordons le problème d'un point de vue général.

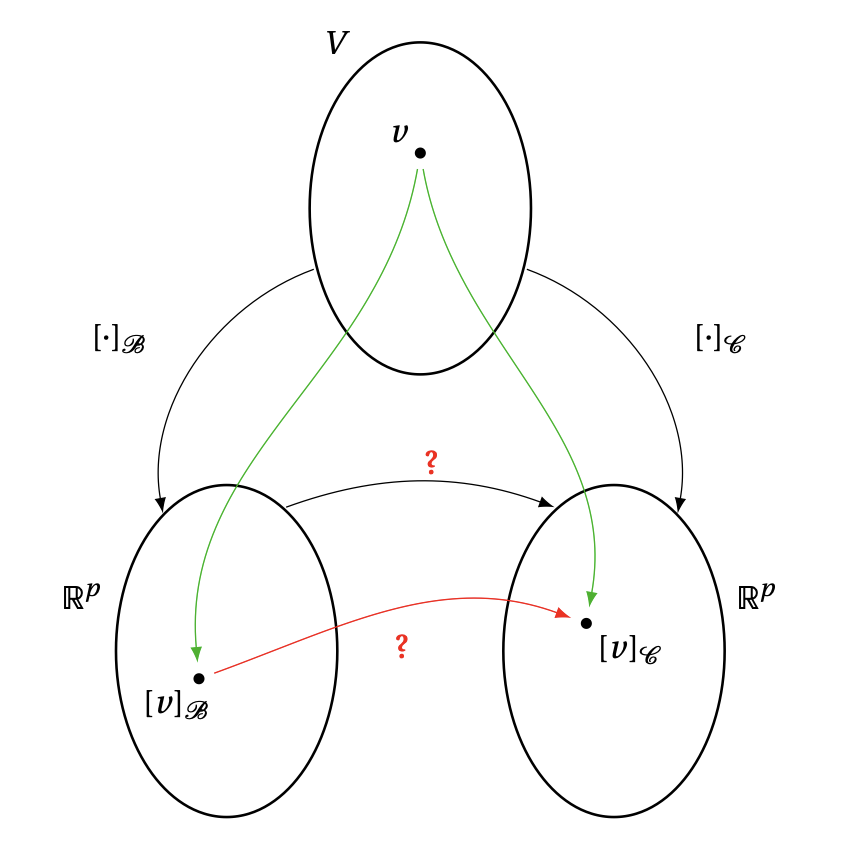

Soit \(V\) un espace vectoriel de dimension \(p\).

Supposons que l'on ait deux bases dans \(V\):

\[

\mathcal{B}=\{ b_1,\dots,b_p\}\,,\qquad \mathcal{C}=\{c_1,\dots,c_p\}\,.

\]

Si \(v\in V\) est un vecteur quelconque, il peut être décomposé dans une base ou

dans l'autre, et les composantes relatives à ces bases seront a priori

différentes:

\[

[v]_\mathcal{B}=

\begin{pmatrix}

\beta_1\\

\vdots\\

\beta_p

\end{pmatrix}\,,

\qquad

[v]_\mathcal{C}=

\begin{pmatrix}

\gamma_1\\

\vdots\\

\gamma_p

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Nous aimerions savoir comment les composantes relatives à

une base, par exemple les

\(\beta_1,\dots,\beta_p\), peuvent se calculer à partir des composantes dans

l'autre base, c'est-à-dire les \(\gamma_1,\dots,\gamma_p\).

Le but de la prochaine sous-section c'est de voir que cette relation est linéaire, et peut donc s'exprimer à

l'aide d'une matrice.

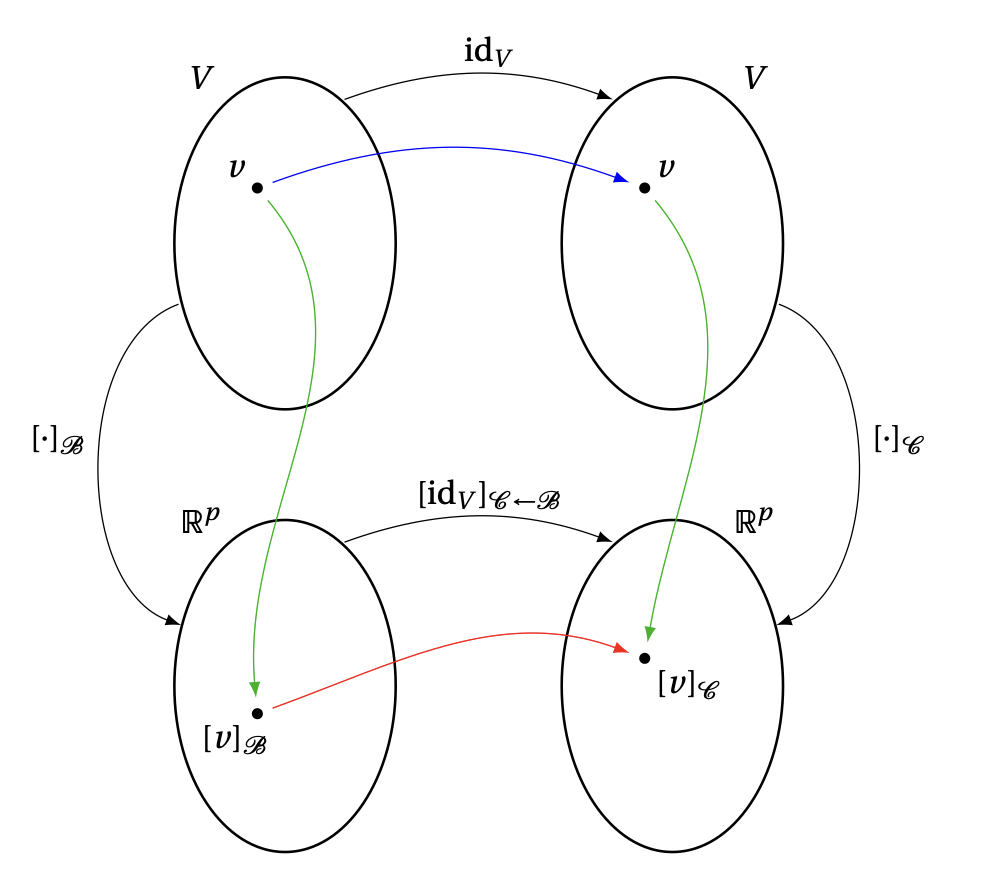

La définition de matrice de passage

On rappelle l'application identité

\(\mathrm{id}_V :V\to V\), définie par

\[

\mathrm{id}_V(v):= v\,,\qquad \forall v\in V\,.

\]

Cette application ne porte en elle rien de vraiment intéressant.

Mais considérons comme avant deux bases pour décrire \(V\), notées

\(\mathcal{C}\) et \(\mathcal{B}\).

Soit \(V\) un espace vectoriel de dimension finie et soient \(\mathcal{B}\) et \(\mathcal{C}\) deux bases de \(V\).

La matrice de passage (ou de changement de base) de \(\mathcal{B}\) vers \(\mathcal{C}\), notée \(P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}\), est définie via

\[

P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}} := [\mathrm{id}_V]_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}.

\]

Étant un cas particulier de représentation matricielle d'une application linéaire,

on trouve immédiatement plusieurs propriétés des matrices de passage.

Soit \(V\) un espace vectoriel de dimension finie et soient \(\mathcal{B} =\{b_1, \dots,b_p\}\) et \(\mathcal{C} = \{ c_1, \dots, c_p\) deux bases de \(V\).

Alors,

- \(P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}=\bigl[[b_1]_\mathcal{C}\cdots [b_p]_\mathcal{C}\bigr]\),

- \([v]_{\mathcal{C}}=P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}[v]_{\mathcal{B}}\) pour tout \(v \in V\);

- \(P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}\) est inversible et

\({P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}=P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{C}}\).

Preuve:

Le premier item suit de la définition de représentation matricielle, vu que

\[

P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}

=

[\mathrm{id}_V]_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}

=\Big[\big[\mathrm{id}_V(b_1)\big]_{\mathcal{C}} \cdots

\big[\mathrm{id}_V(b_p)\big]_{\mathcal{C}} \Big]

=

\bigl[[b_1]_\mathcal{C}\cdots [b_p]_\mathcal{C}\bigr]\,.

\]

Le deuxième item suit de l'identité

du Théorème

dans la Section (cliquer)

pour \(T = \mathrm{id}_V\).

Finalement, comme l'application \(\mathrm{id}_V\) est bijective, le dernier item

de la Proposition

dans la Section (cliquer)

nous dit que \(P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}} = [\mathrm{id}_V]_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}\) est inversible.

En plus, la même proposition nous dit que

\[

P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}^{-1} = [\mathrm{id}_V]_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}^{-1}

= [\mathrm{id}_V^{-1}]_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{C}}

= [\mathrm{id}_V]_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{C}}

= P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{C}}

\,,

\]

où l'on a utilisé dans la dernière égalité que \(\mathrm{id}_V^{-1} = \mathrm{id}_V\).

On peut représenter la matrice de passage de forme graphique via le diagramme suivant.

On présente aussi de façon sommaire le point clé de cette section.

Point clé: Matrice de passage et vecteurs de coordonnées

Pour un espace vectoriel \(V\) de dimension finie, et bases \(\mathcal{B}\) et

\(\mathcal{C}\) de \(V\), on a l'identité fondamentale

\begin{equation*}

\([v]_{\mathcal{C}}

=

P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}

[v]_{\mathcal{B}}\)

\end{equation*}

pour tout \(v \in V\), et \(P_{\mathcal{C}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}\) est l'unique matrice qui

vérifie cette propriété pour tout \(v \in V\).

Exemple:

Dans le plan, considérons comme tout à l'heure le vecteur

\[

\boldsymbol{x}= \begin{pmatrix} 5\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Pour être plus précis, notons \(\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}=\{\boldsymbol{e}_1,\boldsymbol{e}_2\}\) la base canonique,

et récrivons

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} 5\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Considérons maintenant la base \(\mathcal{B}=\{\boldsymbol{b}_1,\boldsymbol{b}_2\}\) définie par:

\[

\boldsymbol{b}_1= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\-1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

\boldsymbol{b}_2= \begin{pmatrix} 2\\1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Calculons \([\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}\), en fonction de

\([\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\), en utilisant le théorème:

\[

[

\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B} =P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}} [\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}} \,,

\]

où

\[P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=\bigl[[\boldsymbol{e}_1]_\mathcal{B}\,[\boldsymbol{e}_2]_\mathcal{B}\bigr]\,.\]

On doit donc

trouver les composantes de \(\boldsymbol{e}_1\) et \(\boldsymbol{e}_2\) relatives

à \(\mathcal{B}\).

Mais comme

\[

[\boldsymbol{b}_1]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=\begin{pmatrix} 1\\-1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{b}_2]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=\begin{pmatrix} 2\\1 \end{pmatrix}\,

\]

signifie en fait

\[

\left\{

\begin{array}{ccccc}

\boldsymbol{b}_1&=&\boldsymbol{e}_1&-&\boldsymbol{e}_2\,, \\

\boldsymbol{b}_2&=&2\boldsymbol{e}_1&+&\boldsymbol{e}_2 \,,

\end{array}

\right.

\]

on a

\[

\left\{

\begin{array}{ccccc}

\boldsymbol{e}_1&=&\frac13\boldsymbol{b}_1&+&\frac13\boldsymbol{b}_2\,, \\

\boldsymbol{e}_2&=&-\frac23\boldsymbol{b}_1&+&\frac13\boldsymbol{b}_2 \,,

\end{array}

\right.

\]

Ainsi,

\[

[\boldsymbol{e}_1]_\mathcal{B}= \begin{pmatrix} 1/3\\ 1/3 \end{pmatrix} \,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{e}_2]_\mathcal{B}= \begin{pmatrix} -2/3\\ 1/3 \end{pmatrix} \,,

\]

et donc

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=\bigl[[\boldsymbol{e}_1]_\mathcal{B}\,[\boldsymbol{e}_2]_\mathcal{B}\bigr]

=

\begin{pmatrix}

1/3&-2/3\\

1/3&1/3

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Donc les coordonnées de \(\boldsymbol{x}\) relatives à \(\mathcal{B}\) sont

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

\begin{pmatrix}

1/3&-2/3\\

1/3&1/3

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} 5\\1 \end{pmatrix}

=

\begin{pmatrix} 1\\2 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

comme nous avions trouvé plus haut.

Si maintenant on souhaite plutôt transformer des

composantes relatives à \(\mathcal{B}\) en des composantes relatives à

\(\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\), on calcule

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}={P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}}^{-1}

=

\frac{1}{1/3}

\begin{pmatrix} 1/3&2/3\\ -1/3&1/3 \end{pmatrix}

=

\begin{pmatrix} 1&2\\ -1&1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Donc si par exemple on prend \(\boldsymbol{x}\) tel que

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=

\begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 2 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

alors ses composantes relatives à \(\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\) sont, comme on sait déjà,

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}

= P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}

=

\begin{pmatrix} 1&2\\ -1&1 \end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 2 \end{pmatrix}

=\begin{pmatrix} 5\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Exemple:

Supposons que l'on considère, dans \(\mathbb{R}^3\), le vecteur

\[ \boldsymbol{x}= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 2\\ 3 \end{pmatrix}\,. \]

Considérons la base de \(\mathbb{R}^3\), \(\mathcal{B}=\{\boldsymbol{b}_1,\boldsymbol{b}_2,\boldsymbol{b}_3\}\),

dont les vecteurs sont

(on laisse au lecteur le soin de vérifier que \(\mathcal{B}\) est effectivement une

base):

\[

\boldsymbol{b}_1= \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

\boldsymbol{b}_2= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ -1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

\boldsymbol{b}_3= \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 2\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Ensuite, cherchons les composantes de \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

relatives à \(\mathcal{B}\), en utilisant le formalisme présenté plus haut.

Pour bien faire, récrivons explicitement ce que nous savons:

\[ [\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 2\\ 3 \end{pmatrix}\,, \]

ainsi que

\[

[\boldsymbol{b}_1]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 0\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{b}_2]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 0\\ -1 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{b}_3]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} 0\\ 2\\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Pour exprimer les composantes de \(\boldsymbol{x}\)

relatives à \(\mathcal{B}\), nous allons utiliser la formule

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}=P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\,,

\]

où la matrice de passage est donnée par

\[ P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

\bigl[

[\boldsymbol{e}_1]_{\mathcal{B}}\, [\boldsymbol{e}_1]_{\mathcal{B}}\, [\boldsymbol{e}_1]_{\mathcal{B}} \bigr]\,.

\]

Or si on écrit explicitement les définitions des vecteurs de la base \(\mathcal{B}\),

\[

\left\{

\begin{array}{ccccc}

\boldsymbol{b}_1 &=&&& \boldsymbol{e}_3\,,\\

\boldsymbol{b}_2 &=&\boldsymbol{e}_1&&-\boldsymbol{e}_3\,, \\

\boldsymbol{b}_3 &=&&2\boldsymbol{e}_2\,.&

\end{array}

\right.

\]

Comme on doit exprimer les composantes des vecteurs de la base canonique par

rapport à \(\mathcal{B}\), il faut inverser ces relations. On trouve facilement

\[

\left\{

\begin{array}{ccccc}

\boldsymbol{e}_1 &=&\boldsymbol{b}_1&+\boldsymbol{b_2}\,,&\\

\boldsymbol{e}_2 &=&&&\frac12 \boldsymbol{b}_3\,, \\

\boldsymbol{e}_3 &=&\boldsymbol{b}_1\,,&&

\end{array}

\right.

\]

c'est-à-dire

\[

[\boldsymbol{e}_1]_{\mathcal{B}}= \begin{pmatrix}1 \\1 \\0 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{e}_2]_{\mathcal{B}}= \begin{pmatrix}0 \\0 \\ \frac12 \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{e}_3]_{\mathcal{B}}= \begin{pmatrix}1 \\0 \\0 \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

ce qui donne

\[\begin{aligned}

[\boldsymbol{x}]_\mathcal{B}

&=P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

1&0&1\\

1&0&0\\

0&\frac12&0

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix} 1\\ 2\\ 3 \end{pmatrix}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix} 4\\ 1\\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Remarque:

Pour le calcul de \(P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\), une façon tout à fait

équivalente de faire mais écrite différemment

aurait été de commencer par calculer

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}=

\bigl[

[\boldsymbol{b}_1]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\, [\boldsymbol{b}_2]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\, [\boldsymbol{b}_3]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}} \bigr]

=

\begin{pmatrix}

0&1&0\\

0&0&2\\

1&-1&0

\end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

puis de calculer son inverse (par exemple avec l'algorithme de Gauss-Jordan):

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

{P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\leftarrow\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}=

\begin{pmatrix}

1&0&1\\

1&0&0\\

0&\frac12&0

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]