8.5 Le changement de base

JE METS CA OU?

On l'a dit, une base permet de représenter les vecteurs d'un espace vectoriel,

de façon univoque.

Pour l'instant, nous avons toujours considéré les vecteurs de

\(\mathbb{R}^n\) comme étant définis à l'aide de leurs composantes relativement à la

base canonique. Cela signifie que lorsqu'on dit qu'un vecteur \(\boldsymbol{x}\) a pour

composantes \(x_1,x_2,\dots, x_n\), cela veut en fait dire que

\[

\boldsymbol{x}=x_1\boldsymbol{e}_1+\cdots +x_n\boldsymbol{e}_n\,.

\]

Donc au lieu de

\[

\boldsymbol{x}=

\begin{pmatrix} x_1\\ \vdots\\ x_n \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

nous aurions toujours dû écrire

\[

[\boldsymbol{x}]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

\begin{pmatrix} x_1\\ \vdots\\ x_n \end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Nous l'avons déjà dit plus haut: les vecteurs existent indépendamment des

composantes que l'on utilise pour les décrire!

Nous allons commencer par exploiter les diverses formules de changement de base

vues dans le chapitre sur les espaces vectoriels, sur quelques exemples

concrets. Nous verrons aussi comment certains problèmes sont plus faciles à

étudier lorsqu'on se place dans une base particulière bien choisie.

Changement de bases: vecteurs

Changement de base pour une application linéaire

Toutes les applications linéaires que nous avons défini jusqu'à présent ont

généralement été définies relativement à la base canonique: leur matrice

s'obtenait en calculant les images des vecteurs de la base canonique.

Mais on sait maintenant exprimer la matrice d'une application relativement à

n'importe quelle base. Nous allons donc repasser par certaines applications

rencontrées précédemment, et étudier leur matrice relativement à des basees qui

ne sont pas canoniques.

Un truc bateau d'une application de \(\mathbb{R}^3\), sans aucun intérêt

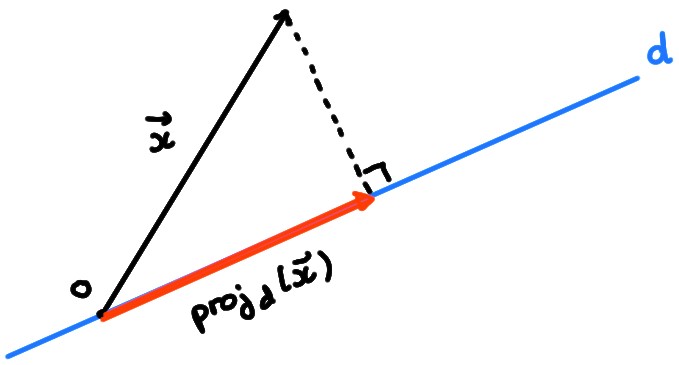

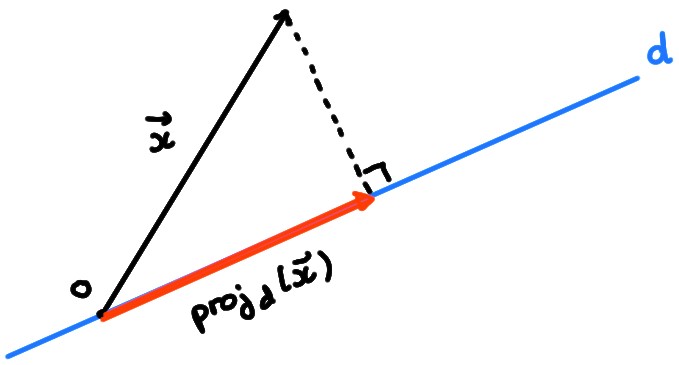

Considérons la projection \(\mathrm{proj}_d\)

sur une droite \(d\) passant par l'origine et faisant

un angle de \(\theta\) avec \(\boldsymbol{e}_1\):

Nous avions trouvé la matrice suivante relativement à la base canonique:

\[

[\mathrm{proj}_d]_{\mathcal{B}_{can}}

=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos^2\theta&\cos\theta\sin\theta\\

\cos\theta\sin\theta&\sin^2\theta

\end{pmatrix}

\]

L'allure un peu compliquée de cette matrice est due

au fait que l'on a exprimé cette matrice relativement à une base qui n'est pas

naturelle: relativement à \(\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}=(\boldsymbol{e}_1,\boldsymbol{e}_2)\), \(d\) est inclinée.

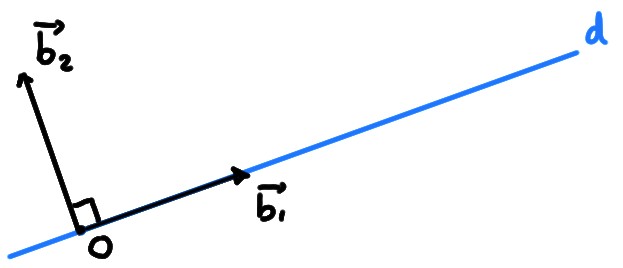

Plus naturelle, pour décrire cette projection, serait une

base dans laquelle les vecteurs sont orientés dans des directions qui tiennent

compte de la position de l'axe \(d\). Par exemple, une base

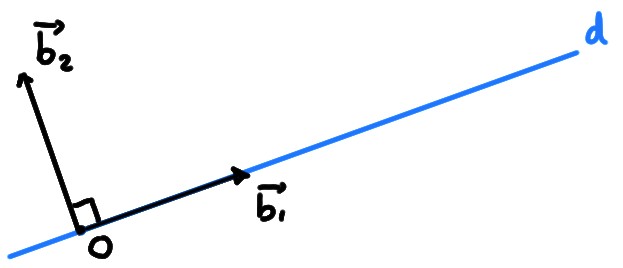

\(\mathcal{B}=(\boldsymbol{b}_1,\boldsymbol{b}_2)\) où \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) dirige \(d\), et \(\boldsymbol{b}_2\)

est perpendiculaire à \(d\):

Puisque \(d\) fait un angle \(\theta\) avec l'horizontale, en les prenant

orientés comme sur la figure ci-dessus, et unitaires,

\[

[\boldsymbol{b}_1]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} \cos\theta\\ \sin\theta \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{b}_2]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} -\sin\theta\\ \cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Ainsi, la matrice de changement de base est

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos\theta&-\sin\theta \\

\sin\theta & \cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

que l'on va utiliser dans la formule de changement de base:

\[

[\mathrm{proj}_d]_{\mathcal{B}}

=

{P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}}^{-1}

[\mathrm{proj}_d]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}\,.

\]

On trouve

\[\begin{aligned}

[\mathrm{proj}_d&]_{\mathcal{B}}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos\theta&\sin\theta \\

-\sin\theta & \cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos^2\theta&\cos\theta\sin\theta\\

\cos\theta\sin\theta&\sin^2\theta

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos\theta&-\sin\theta \\

\sin\theta & \cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

1&0\\

0&0

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Dans cet exemple, on a juste observé que la projection prenait une forme plus

simple quand on la regardait dans une base qui était adaptée à la géométrie du

problème. Faisons maintenant l'inverse: prenons une transformation, définie dans

une base simple, et voyons quelle forme elle prend dans une base plus

compliquée:

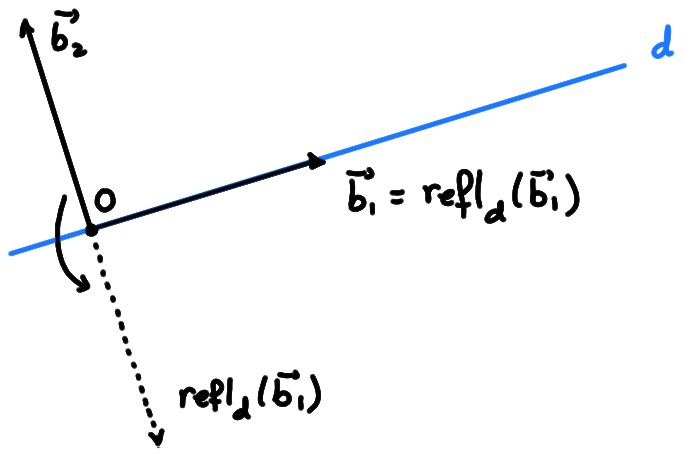

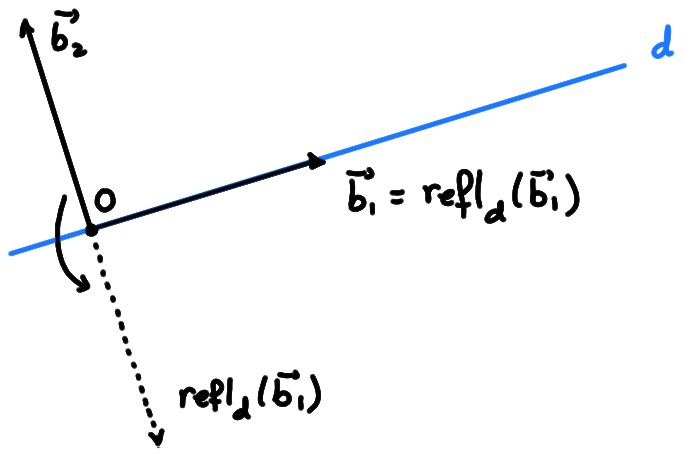

Considérons la

réflexion par rapport à une droite \(d\) qui passe par

l'origine, que nous avions notée \(\mathrm{refl}_d\).

Utilisons à nouveau la base

\(\mathcal{B}=(\boldsymbol{b}_1,\boldsymbol{b}_2)\) où \(\boldsymbol{b}_1\) dirige \(d\), et \(\boldsymbol{b}_2\)

est perpendiculaire à \(d\). On remarque que l'application de la réflexion sur

ces vecteurs prend une forme très simple:

\[

\mathrm{refl}_d(\boldsymbol{b}_1)=\boldsymbol{b}_1\,\qquad

\mathrm{refl}_d(\boldsymbol{b}_2)=-\boldsymbol{b}_2\,.

\]

Par conséquent,

\[

[\mathrm{refl}_d]_{\mathcal{B}}=\bigl[[T(\boldsymbol{b}_1)]_\mathcal{B}\,[T(\boldsymbol{b}_2)]_\mathcal{B}\bigr]

=

\begin{pmatrix}

1&0\\

0&-1

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

À partir de cette expression simple, exprimons

la matrice de \(\mathrm{refl}_d\) relativement à une autre base, par exemple la base

canonique:

\[

[\mathrm{refl}_d]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}=

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}

[\mathrm{refl}_d]_{\mathcal{B}}

P_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\,.

\]

Or

\[

[\boldsymbol{b}_1]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} \cos \theta\\ \sin \theta \end{pmatrix}\,,\qquad

[\boldsymbol{b}_2]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}= \begin{pmatrix} -\sin\theta\\ \cos\theta \end{pmatrix}\,,

\]

et donc

\[

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos \theta&-\sin\theta\\

\sin\theta&\cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\]

Comme cette dernière est une matrice de rotation (d'un angle \(\theta\)), son

inverse est la matrice de rotation d'angle \(-\theta\). On a donc

\[\begin{aligned}

[\mathrm{refl}_d]_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}&=

P_{\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}\mathcal{B}}

[\mathrm{refl}_d]_{\mathcal{B}}

P_{\mathcal{B}\mathcal{B}_{\mathrm{can}}}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos \theta&-\sin\theta\\

\sin\theta&\cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix}

1&0\\

0&-1

\end{pmatrix}

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos \theta&\sin\theta\\

-\sin\theta&\cos\theta

\end{pmatrix}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos^2\theta-\sin^2\theta&2\sin\theta\cos\theta\\

2\sin\theta\cos\theta&\sin^2\theta-\cos^2\theta

\end{pmatrix}\\

&=

\begin{pmatrix}

\cos(2\theta)&\sin(2\theta)\\

\sin(2\theta)&-\cos(2\theta)

\end{pmatrix}\,.

\end{aligned}\]

Cette expression est bien celle que nous avions obtenue précédemment.